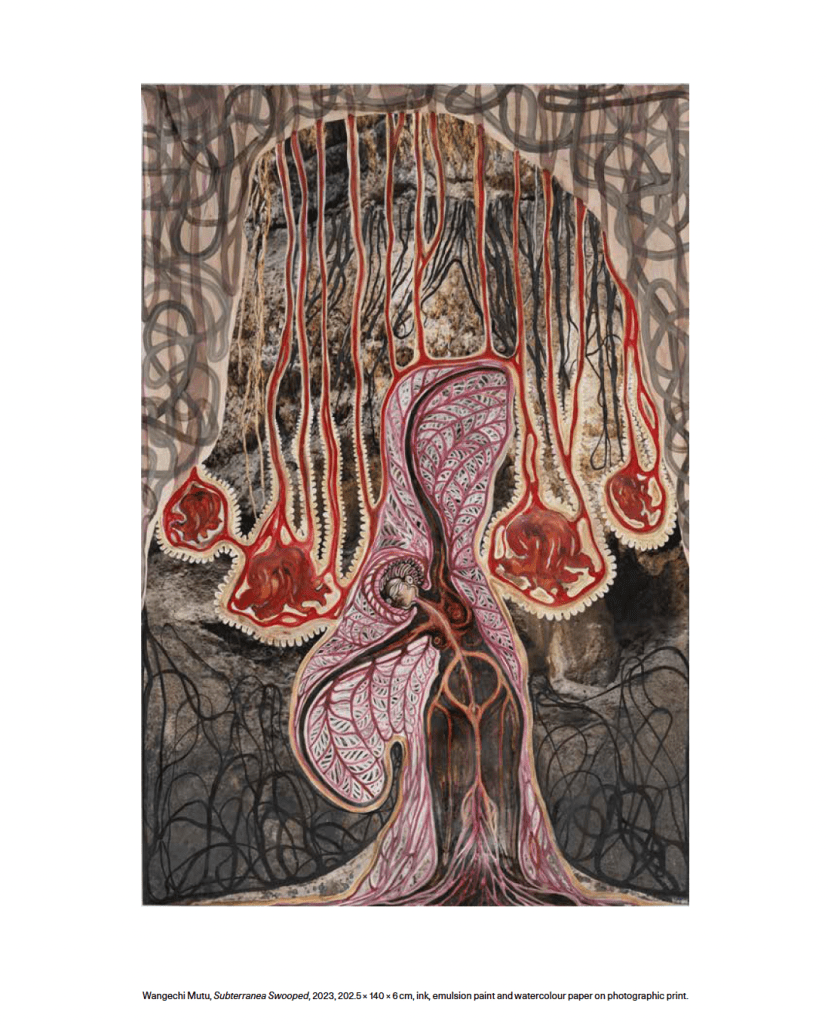

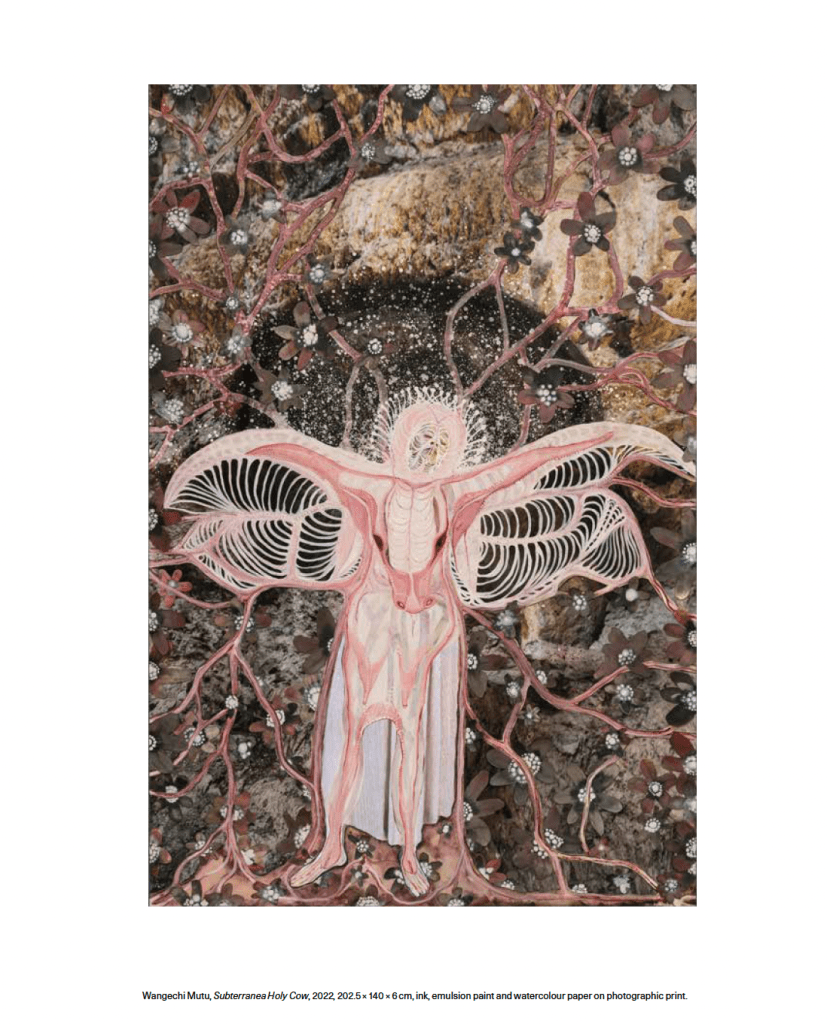

Wangechi Mutu is a Kenyan-born, New Yorkbased artist whose work is renowned for its forceful critique of power, politics and identity. With a multi-disciplinary practice that spans drawing, collage, video and performance, Mutu creates fantastical and surreal landscapes that challenge the dominant narratives of the Western art world. Through her unique visual language, she draws upon a rich tapestry of cultural and historical references and her own experiences as a diasporic African woman to explore the intersections of race, gender and colonialism, while also drawing attention to the complexities of the human condition. Mixing sensuality and violence, Mutu’s work is equally seductive and disturbing, speaking directly to the viewers’ subconscious and inviting them to question their own perceptions. Her work has been displayed in major exhibitions and galleries around the world, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco and the Centre Georges Pompidou.

Michele Fossi: One of the most striking elements of your art is the way you represent women. Your female figures are often depicted through collage techniques as powerful, larger-than-life beings with exaggerated features and poses. Strong, assertive, unapologetic, and sometimes even threatening, they challenge traditional notions of femininity and beauty. Who are they, and what do they represent to you?

Wangechi Mutu: Growing up around strong African black women, my work celebrates them and what they have helped me achieve. This is my way of honouring and praising all the strong black women throughout the centuries who helped us get to this point in history. We all originated from African ancestors; every single one of us comes from the same common black mother. Dispersions and migrations began thousands of years ago with people migrating from their motherland to colder, less sunny regions or to other faraway continents. Despite our differences, we are all part of the same homo sapiens species.

Michele: How did you develop this strong interest in the black female figure?

Wangechi: I attended a Catholic all-girls school where I was surrounded by female teachers, female students and images of the Virgin Mary. This immersive environment, steeped in feminine energy, has been an enduring source of inspiration for me. I view feminine energy as a universal aspect of humanity, one I continually attempt to incorporate into my works.

Michele: What led you to choose collage as your artistic medium at the beginning of your career?

Wangechi: I chose collage as my medium because it was the most accessible and impactful way for me to create. When I moved to New York and aimed to become a serious artist, I lacked the resources for expensive materials. I started experimenting with magazine clippings and watercolours, which led to unexpected surprises and a sense of tension that I sought in the creation process. By combining these elements, I was able to create something new that even I had to understand.

Michele: Is it possible for you to quickly walk us through some of the most unusual materials you use in your collages and explain their function?

Wangechi: I have worked with milk, wine, high heels, soil, trash bags, tea leaves, hair nets, buttons, cow horns, shells, moths, panties, and crystals to represent the beauty and potential of this diverse world.

Michele: What about the photographic material you incorporate, mostly portraying black women?

Wangechi: The majority of the photographic elements in my collages were sourced from fashion magazines. I then expanded my search to include other types of magazines, moving away from the idealised and homogenous depictions of women in glossy glamour magazines. I observed how skin types were portrayed differently based on the intended audience and what was being sold. This sparked a creative challenge for me, as I sought to subvert the original narrative and craft something dignified, beautiful and alluring from images that once bothered me.

Michele: Your female figures exude an otherworldly and surreal quality, enhanced by the incorporation of human and animal features, such as women with hyena heads or manta ray bodies.

Wangechi: The blending of human and animal elements is as old as the human imagination itself. Throughout history, humans have been enamoured with the elegant grace, speed and raw strength of certain creatures, and have often sought to embody these qualities in their own form. My art is deeply inspired by the natural world and I am particularly drawn to the ways in which all living beings, including humans, animals and plants, are interconnected and interdependent on this crowded planet. Despite the destruction wrought by humans, if you take the time to observe and contemplate, it becomes clear that all living creatures, animals, people and plants stem from a common origin and share the earth’s resources.

Michele: In 2014, at Victoria Miro Gallery, you showed Sleeping Serpent, a fabric and ceramic sculpture over ten metres long, of a snake with a woman’s head. Such human-snake hybrid creatures are recurrent in your work.

What are they?

Wangechi: They are inspired by the real-life giant sea cow known as the nguva, which is native to East Africa and has become increasingly rare due to overhunting. In local folklore, these marine animals are intertwined with mythology, being believed to possess the ability to transform into mermaid-like human forms. The belief in these magical creatures is becoming less widespread, with fewer people in Kenya openly discussing the mermaids. In the past, sightings of beautiful new women in a village would often be met with whispered warnings of ‘She must be a nguva.’

Michele: No less mesmerising are The Seated, four bronze sculptures you created for the Met’s facade niches in September 2019, a space that has been vacant since the museum was built. Titled The NewOnes, will free Us, the works consist of two kneeling and two seated female figures, exuding regal power. They have been described as ‘simultaneously celestial and humanoid, strange and familiar’, as well as ‘the culmination of two decades of sustained artistic experimentation and rigorous research into the relationship between power, race, gender, and representation’. What inspired the idea for this special commission?

Wangechi: When the Met approached me with this opportunity, I delved into the study of the caryatid sculptures housed in their museum. Historically, caryatids were used to showcase the power and wealth of a particular place through their supporting role in architecture. This idea is echoed in African sculptures, which frequently feature sitting or kneeling female figures holding up the throne of a king and sometimes even a child. Upon realising that this was a typical portrayal of women across various cultures and time periods, I wondered how I could use this figure to challenge and subvert these cultural norms. I wanted to retain the strong and active pose of the woman, but I did not want her to be burdened with carrying the weight of something or someone else.

Michele: What are those coils and discs decorating them?

Wangechi: I’ve incorporated coils that wrap around the female figures to give them a tactile and fleshy quality. At the same time, these coils provide a sense of protection and privacy, giving the women a regal and almost armoured appearance. The discs that adorn their bodies were inspired by the stunning lip plates worn by women of high status in Ethiopian and Sudanese tribes. In my interpretation these disks serve as mirrors, reflecting and twisting light to captivate the viewer from a distance.

Michele: You divide your time between two studios, one in New York and one in Nairobi. Are there similarities between the two?

Wangechi: Both my Nairobi studio and the New York studio are filled with similar material: photographic books about Africa’s history and traditions, pictures of current affairs, magazines, et cetera. The walls, which I see as thinking space, are also usually filled with images. The main difference between the two is that I am surrounded by natural soil, rocks and plants in Nairobi. To get the supplies for my work I just need to walk out the door of the studio.

Michele: You are known for having a very intimate relationship with your studio.

Wangechi: My studio is a crucial part of my daily routine, it’s where I feel the most focused and comfortable. Only my close family and assistant are allowed in, creating an intimate atmosphere. The fact that my studio is close to my home adds to its significance in my life, serving as both the heart and soul of my daily existence. I view my studio as a sacred space, where I can think and create in a different manner than I do in other environments. It is a mental space that stimulates my imagination, and I consider it a place to be honoured and respected.

Michele: As a Kenyan-born artist residing in the US, has your nostalgia for Kenya influenced your art, and if so, how?

Wangechi: My work often reflects feelings of nostalgia, saudade and ennui. It’s difficult to depart from one’s home country, especially when the future is uncertain. I find myself frequently missing my childhood home and the memories associated with it. The plants, flowers and creatures in my work are sourced from these memories, representing a longing for a time that no longer exists.

Michele: Staying on the topic of interiors, the theme of this issue of Acne Paper is ‘House’. What memories do you have of your childhood house?

Wangechi: My family and I lived in a little one-story bungalow surrounded by a garden. I remember playing on the dry grass with our toys, sometimes in areas of the garden where we weren’t supposed to. It was a bit of a wild space, where we got very dirty. The memories I have of that time have influenced the way I work today.

Michele: You seem to draw a lot of inspiration from that little girl playing on the grass in your artistic practice. You frequently incorporate ‘fragments of Nature’ and other found materials into your work to emphasise the cyclical nature of life and the interdependence of all living things, and to explore themes of birth, growth, decay and renewal, while also commenting on the impact of human behaviour on the environment.

Wangechi: As an artist, I have a strong belief in the transformative power of collage. By taking pieces of nature, like trees and animals, and anonymous yet recognisable objects and placing them in my work, I aim to magnify their energy and essence. By incorporating them into my art, I aim to highlight the importance of every living being in maintaining a delicate balance in our ecosystem. Through my work, I strive to amplify the significance of each plant, animal and human, and to showcase the interconnectedness of all life.

Michele: Inorganic material such as soil and mud also often appears in your mixed-media collages and sculptures as a symbol of the connection between humans and the natural world, as well as a metaphor for identity and cultural heritage.

Wangechi: Soil has become important for me and this Nairobi studio because I actually identify with the soil. Soil that I remember from my childhood, the colour of the soil, the feeling of the soil, the texture, the way it behaves when it’s dry, when it’s wet, when it rains. In New York, I don’t feel that same sense of identification with the soil. I don’t trust the soil. I always think that there are other things going on in this soil that I haven’t put in and weren’t put in there in the first place by nature. So there is a certain diffidence between me and the ground. Whereas here I tend to immediately want to capture the essence of the soil, the malleability, the colour, the crispness, the granular aspects. All of those things are important for me in the work.A

Michele: You also produced a few impressive animated videos. The first one, called ‘The End of eating Everything’, was created in collaboration with recording artist Santigold and co-released by the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University in 2013. It shows the journey of a monstrous, flying, planet-like creature with a beautiful female face, navigating a bleak and polluted sky-scape and relentlessly devouring birds. Is it a representation of humanity’s omnivorous appetite for things in the world?

Wangechi: The concept behind this piece was to bring a collage to life in four dimensions. As I worked on it I realised that what I’d created was more than just a monster – it was like a moon or a planet. This creature symbolises human evolution, as well as consumption, greed and industrialisation. In the end, exhausted, it consumes itself until oblivion, and collapses in its own waste and smoke.C

Michele: The animated video ‘The End of carrying All’, first presented during the Venice Biennale in 2015, features a female figure who is carrying a large, cumbersome burden on her shoulders. The figure’s journey is meant to comment on the experiences of women and people of colour, who are often burdened with societal expectations and injustices.

Wangechi: The burden the woman carries – a symbol of labour as well as the struggles of civilisation and industrialisation – becomes increasingly heavy. On her head, she carries a radio tower, a large TV dish, an apartment building, an oil rig, and more. As she travels through a stunning sunset landscape, she eventually collapses from exhaustion. Despite this, she continues to move forward, even resorting to crawling. At this point, we realise that what we are witnessing is not just the representation of man-made problems, but something else entirely – a growing anomaly that ultimately overflows and engulfs her. C

Michele: The conversation about the representation of black women of colour has accelerated in recent years. Having worked on this topic for over twenty years, how do you see things evolving?

Wangechi: We are gradually moving towards a more inclusive society, but progress is slow because equality contradicts capitalism’s reliance on inequality and unfairness. It’s time to acknowledge the truth about how we got here, including calling out abusive leaders and admitting the injustices committed against marginalised communities for the sake of wealth. We must reject the notion of white European supremacy and embrace the diversity of our world. I am inspired by women who are breaking barriers and becoming leaders in influential positions in companies, departments, governments and cities. Diverse representation is essential for ensuring that diverse perspectives are included in shaping our future. I am a firm believer in our interconnectedness, which is why I am drawn to mixed-media art forms such as collage and assemblage. I see strength in diversity, as homogeneity leads to weakness. The only way to bring about change and empower each other is through collaboration.”

Published in ACNE PAPER #18, June 2023